Cultural experiences often cause sizable differences in worldviews. Something normal in one culture can violate a significant norm in another culture, making it difficult to build trust in relationships. Bridging this divide takes effort, patience, and openness, and is the only way to build long term trusting relationships. Sharing, especially through listening and understanding the experiences of others, helps to close the gap and transcend differences.

I learned this lesson during my time in Papua New Guinea where I had to confront our core team tribal village members over the theft of company funds by the second-highest-ranking company member. Even though I had no real grasp of Barai, the common language in the village, I still had to work through all the steps to build trust, break through the culture of loyalty over truth and lead them into an accountability discussion where they could grasp the importance of honesty and integrity. This allowed them to accept the consequences of him breaking the law.

How does one find the path to be authentic and at the same time authoritative in an organization of such a different cultural setting? A culture where very few people had interactions with communities outside their own clans? Where their own mind-set was quite restricted by their own limited experiences of other cultures and other values? How do you achieve agreement on difficult and complex issues when perspectives, norms and culture are so dissimilar and mismatched?

In the simplicity and truth of my experience in the remote Papua New Guinea rainforest village of Tabuane, Oro Province (where cannibalism ceased only as recently as 1963), I was able to transcend the differences and find what we had in common – and share it.

The experience is described in my book Tau Bada: The Quest and Memoir of a Vulnerable Man:

I have reconstructed the toktok [open talking session] that took place in Tabuane on Saturday, May 7, 2011.

John: I would like to thank you for being here today. The words “truthfulness” and “openness” are important for us to understand together. Without these, our talk today will not be a good talk. What do these words mean to you?

Note: The norm setting and use of metaphors served as my reference point for this meeting. The first thirty minutes were utilized in this introductory exchange. I was slow, deliberate, and precise. The interpreters appeared to be effective.

Group: What do they mean to you, John?

John: Truthfulness is being willing to share what you feel and think and believe what is right and what is wrong. Openness is being willing to listen and respect the other individual saying it to you.

Group: We understand what these words mean, but these are difficult things to do with each other. We do not do this very often in public. It is not comfortable.

Note: An hour of lively discussion unfolded in this subliminal and inclusive introduction. Consensual communication was reinforced as everyone stood and spoke in turn.

John: I think it is important to tell you the truth about Juda Divish—how his actions hurt this company, you, and the farmers. Do you want to hear this truth and be open to hear what I will say?

Group: Yes, John, we want to hear the truth. We are very upset. Where is our money? Where is our compensation? Where are the payments for the farmers?

Note: Thirty minutes transpired for safety, survival, and gratification themes to emerge. Cash is scarce. This is survival instinct in an unvarnished response.

John: Java Mama [my company] believes in honesty. We do not cheat, rob, or steal. We are an honest company. Truthfulness is like one of your house poles. The pole supports your home. Without it, your house will fall. Is this true?

Group: It is like a strong pole. Yes, without honesty the company will fall like our house.

Note: Fifteen minutes of consensus-building took place. The analogy of the pole was helpful for them to grasp this value labeled honesty.

John: Juda made me angry and sad. He stole fifteen thousand kina. This money was for your compensation and payment to your chilies farmers. He stole the money to buy gold for himself. We know who did this with him. We got a confession statement from him as well as witness statements. I had him arrested, and he is in a cell in Popondetta. He will appear before a magistrate and will be put in prison. Do you have any questions? Do you understand now what happened? Do you agree the company did the right thing?

Group: (Silence. A shaking of heads and then multiple conversations among the members.)

Note: Another twenty minutes passed, giving them the opportunity to be open in public with one another. I retreated as I viewed these interactions. This was a unique fishbowl to observe. The tribal clan’s “ethnocentricity” was pronounced and was a critical juncture of the session. The wantok (we) vs. the company’s welfare (they) was front and center. The contrast of values and behaviors of the host community versus the outside institutional value system was marked.

John: Who wants to speak? Please share your truth, your opinion, and let’s be open and respectful of one another.

Group: I am very angry. We are angry. He did the wrong thing. The farmers need to know what happened. Juda should be ashamed. Now we know the truth. John and Fiona did not hurt us. When are payments going to be made to the farmers? When do we get our compensation? Who is the new boss?

Note: This communal venting process lasted thirty minutes. The responses were thematic. As the meeting progressed, the safety and trust increased, permitting commitments to future actions to evolve.

John: Are we in agreement that this action toward Juda’s wrongdoing was the right thing to do?

Group: Yes, it was the right thing to do. I agree. We agree. He did the wrong thing. He was stupid.

Note: Every member spoke. The yelling, venting, warnings, and affirmations lasted for an hour. The meeting was animated and reverberated with persuasive gestures. Strong confrontation followed by immediate resolution was characteristic. It was a satisfaction sought by all of the participants. This social process was dignifying. I observed a solemn peer respect. Individual voices were heard with solemnity. They facilitated their own meeting. It was a normative process that afforded everyone the chance to be heard, with or without eloquence. No one was made to look or feel foolish.

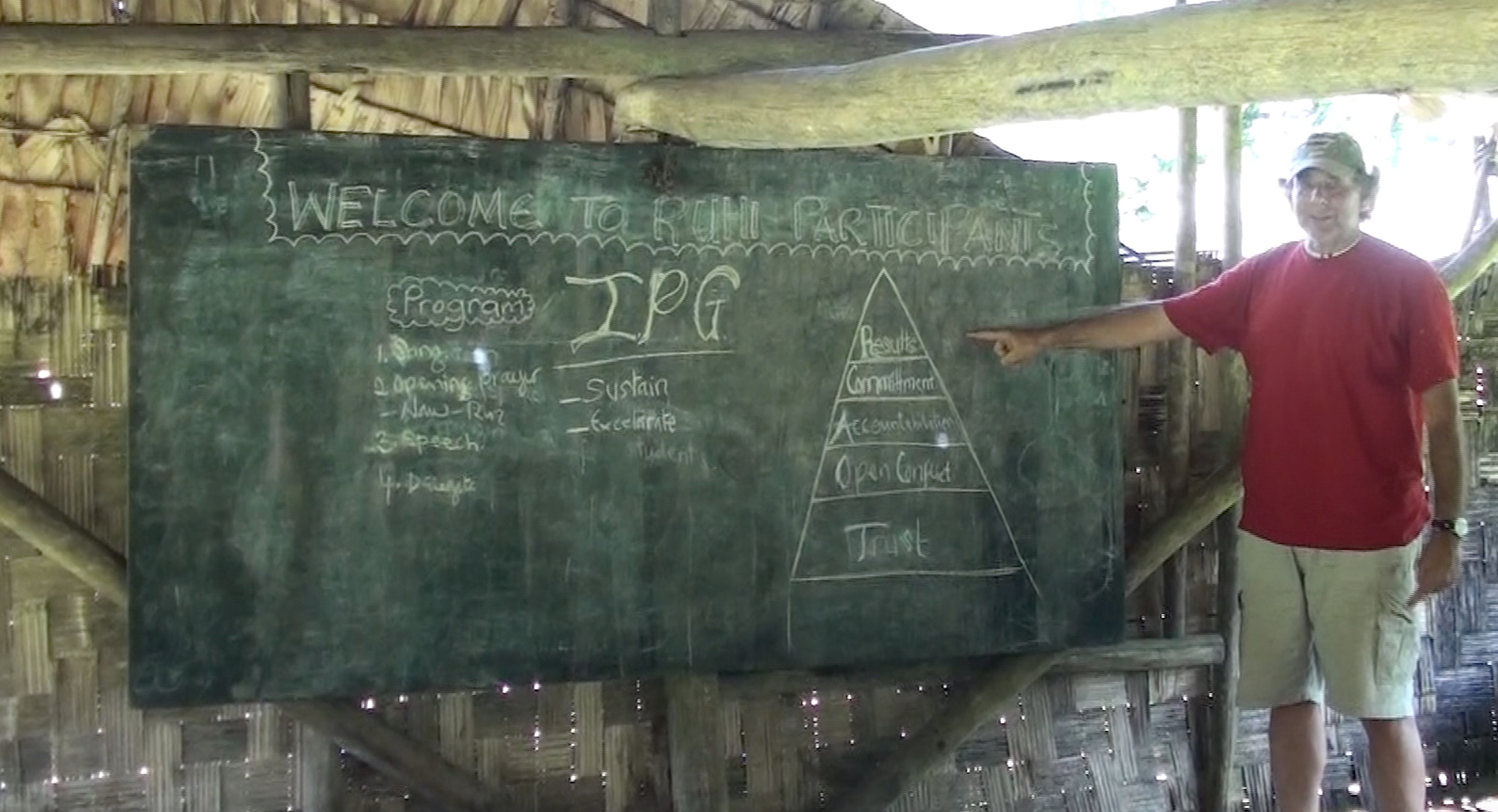

A video from the ebook showing some of our typical meetings:

https://vimeo.com/taubada/review/196770711/06576d5c5a

Although this scene played out in a remote village in PNG, such situations are in constant play in all our cultures. The organization or society that knows how to reach out with integrity and authenticity to understand and then to transcend the differences, with a leader who cultivates and encourages empathy, vulnerability, honesty and trust, is an organization or society that is adaptive and strong enough to navigate today’s changing business and societal landscapes, to allow the best values to come through and permeate the culture and the organization, leading to more fulfillment, productivity and harmony.

My story offers anecdotal evidence related to the power of trust. For those interested in data, there’s science to prove the point. The Harvard Business Review Jan.-Feb. 2017 article “The Neuroscience of Trust” highlights this: “A culture of trust is what makes a meaningful difference. Employees in high-trust organizations are more productive, have more energy at work, collaborate better with their colleagues, and stay with their employers longer than people working at low-trust companies.”

As part of testing their assumptions, the authors travelled to many countries including remote village communities in Papua New Guinea, a country of eight million people speaking in 800 languages. In the authors’ words: “ … We obtained permission to run experiments at numerous field sites where we measured oxytocin and stress hormones and then assessed employees’ productivity and ability to innovate. This research even took me to the rainforest of Papua New Guinea, where I measured oxytocin in indigenous people to see if the relationship between oxytocin and trust is universal.” (It is.) “

Creating a value system that builds trust and fosters open communication is necessary for any successful executive, whether you work in a corporate office or the middle of the rainforest, as my story demonstrates. Developing this personal value system, and determining how it applies to the business world, is a key component of my business consulting and executive coaching practice. My experiences in a country both physically and culturally a world away has taught me how vulnerability and empathy, through open and active listening, build understanding and trust among people who have lived vastly different lives.